Item Details

Work details

- Title

- Aberuthven Parish Church (also known as Abruthven)

- Work OCR text

SUMMARY DESCRIPTION

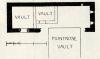

Much of the east, north and west walls, along with the western part of the south wall, survive of the rectangular medieval church. Projecting from the south side is the mausoleum of the Dukes of Montrose, while two burial enclosures now occupy the western part of the nave.

HISTORICAL OUTLINE

The church of St Cathan of Aberuthven was in existence before 1171, it being stated in the charter of c.1198 by which Gillebrigte, earl of Strathearn, granted the church to the monastery at Inchaffray that included in the gift were not only all the teinds, obventions and oblations pertaining to Aberuthven but also the land which his father, Earl Ferteth (d.1171), and mother, Countess Ethne, had given it in dower.(1) The grant was confirmed by King William at Scone on 5 September 1198.(2) When the Céli Dé community at Inchaffray was re-founded as an Augustinian priory in 1200, Aberuthven was named amongst the possessions of the successor convent.(3) It was probably at this time that Bishop Jonathan of Dunblane (1195 x 1198-1210) confirmed the canons’ right to the teinds of the earl’s cain and other rents due to the church of Aberuthven, but it was not until his successor, Bishop Abraham, explicitly confirmed the church in proprios usus to the convent in c.1211 that the parsonage was certainly appropriated to the monastery.(4)

In the 1230s, when Bishop Clement of Dunblane (1233-58) was attempting to secure the precarious finances of his see, the second teinds of Aberuthven became a source of dispute between the canons of Inchaffray and the bishop. In 1234, Bishop Clement initiated litigation in which he claimed that the second teinds of both Aberuthven and Tullidene, another parish church in Strathearn which his predecessors had appropriated to Inchaffray, pertained to him and not the canons.(5) A compromise, however, was settled by which it was agreed that the bishop would drop his claim in return for an annual payment of £16 by the canons. Having secured this concession, Bishop Clement granted the canons, in recognition of the poverty of the monastery, a remission of £6 on the sum due to him, until such time as they had secured appropriation of any of five further churches in Strathearn in which they already held rights.(6) In February 1239, the dean and chapter of Dunblane confirmed the full appropriation of ten parish churches in the diocese, including the church of Aberuthven, to the uses of the canons of Inchaffray.(7)

Probably since 1200 and certainly from 1239 when the confirmation of appropriation by the dean and chapter of Dunblane expressly required it, the parochial cure of Aberuthven was served by a vicarage portionary. There is no evidence of any later attempts to secure the appropriation of the remaining vicarage teinds also, and the thirteenth-century arrangements remained in place at the Reformation. At that time the vicarage, valued at £40 annually, pertained to Mr Robert Henderson, from whose revenues one third was assigned for the support of a curate.(8)

ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION

The medieval church, which was constructed of pink rubble with limited dressings, is a rectangle of 19.6 metres from east to west by 6.67 metres from north to south. The east wall has the only surviving medieval openings, in the form of a pair of small ogee-headed windows which, by analogy with related windows at Mugdock Castle, for example, may indicate a date in the later fourteenth century for the eastern parts of the building. Internally the two embrasures are bridged by lintels which, rather inexplicably, are set at different heights. The windows appear to have been closed by shutters of some kind, which fitted into rebates and were hung from hooks. At the base of the gable externally there has been a chamfered intake, from which most of the dressed stone has been robbed.

As was common, the north wall has no openings, and the only internal feature in this wall is a small aumbry towards its east end, which is rebated for a door frame, and which in this position may have served as a Sacrament House. The rise of internal ground levels following abandonment is clearly indicated by the way in which only the upper part of this aumbry is now exposed. Parts of the north wall may have been reconstructed when burial enclosures were formed in the nave. The west gable is probably the result of a late medieval rebuilding in its present form, and the cavetto-moulded skewputts are in two stepped sections, one corresponding to the coping on the outer face of the gable and the other to the section of roof that extended across the inner part of the wall head. In the lower part of this wall is the curious feature of a pair of square openings that appear to be putlog holes. Pairs of openings of this kind are also found elsewhere in Perthshire at Auchterarder and Inchmartin, for example, though their function is uncertain. Surmounting the west gable is a bellcote of 1721-5 that was built by the masons David Fenton and Robert Richard.

Of the south wall only a short stump survives at the east end, though there is a length of about 7.3 metres at the west end, the latter having been extensively rebuilt when a four-centred-arched doorway was inserted as the entrance to the Graeme burial enclosure in the western part of the nave. That doorway, and the enclosure behind it, appears to date from the earlier nineteenth century, as does the narrower Duff-Duncan burial enclosure to its east. Both those enclosures have been recently re-roofed as part of a programme of stabilisation of the church fabric. The most prominent post-medieval addition to the church was the elegant mausoleum of the dukes of Montrose, which was built to the designs of William Adam in 1736-8. It is an imposing ashlar-built structure of 7.3 metres square which projects south from the line of the south wall of the church; it has a Serlian tripartite opening in its south face and is capped with a pyramidal roof surmounted by an urn.

At an uncertain date following the Reformation the parish of Aberuthven was united with that of Auchterarder, though it is uncertain when the church at Aberuthven passed out of use. The New Statistical Account of 1845 states that the minister’s manse continued to be at Aberuthven and that he had continued to preach there. It also seems that the Montrose mausoleum must have been built at a time when the church was still structurally complete, since it can be seen that it was originally bonded in on both sides with the south wall of the church, and that its two northern angles had to be made good when the adjoining sections of church wall were taken down. Perhaps of greater significance is the way in which it appears that the mausoleum was intended to open into the church through a broad arch in its northern wall, which had to be later blocked. On that basis it would seem that it had been built as a particularly imposing example of a laird’s aisle, with a space for the laird’s pew at the main level, above a subterranean burial vault, indicating that the church must still have been in at least limited use at the time of its construction. Since the central opening of the Serliana in the south wall was adapted as a doorway in 1758, by John Steven, it may have been only as late as then that the internal connection with the church was severed and that there was a need for a separate entrance into the aisle, all of which left it as a free-standing mausoleum rather than as a structurally engaged laird’s aisle.

NOTES

1. Inchaffray Charters, no III.

2. RRS, ii, no 403.

3. Inchaffray Charters, no IX.

4. Inchaffray Charters, nos X, XXX.

5. Inchaffray Charters, no LX.

6. Inchaffray Charters, no LXI.

7. Inchaffray Charters, no LXVII.

8. Kirk (ed.), Book of Assumptions, 334.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Charters, Bulls and other Documents relating to the Abbey of Inchaffray, 1908, (Scottish History Society), Edinburgh, nos III, IX, X, XXX, LX, LXI, LXVII.

Cowan, I.B., 1967, The parishes of medieval Scotland, (Scottish Record Society), Edinburgh, 4.

Gifford, J., 2007, The Buildings of Scotland, Perth and Kinross, New Haven and London, 147-8.

Kirk, J., 1995, The books of assumption of the thirds of benefices, (British Academy) Oxford, 334.

Lindsay, I.G. 1950, ‘The kirks of the diocese of Dunblane’, Society of Friends of Dunblane Cathedral, vol. 6/1, 11.

MacGibbon, D. and Ross, T., 1896-7, The ecclesiastical architecture of Scotland, Edinburgh, vol. 3 1897, 485-6.

Mackinlay, J.M., 1914, Ancient church dedications in Scotland, non-scriptural dedications, Edinburgh, 110.

New Statistical Account of Scotland, 1845, Edinburgh and London, vol. 10, 290.

Regesta Regum Scottorum, Acts of William I (1165-1214), 1971, Edinburgh, no 403.

Reid, A.G., 1899, Annals of Auchterarder, Crieff, 25.

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, Canmore database.

Statistical Account of Scotland, 1791-9, ed. J. Sinclair, Edinburgh, vol. 4, (1792), 44.

- Work Additional Notes

Dedication: St Cathan

Diocese: Diocese of Dunblane

County: County of Perthshire

Council: Perth and Kinross Council

OS: NN 9735 1509

Image details

- Description

- 12. Aberuthven Church, plan (MacGibbon and Ross)

- Full Image Dimensions (WxH)

- 716x420 pixels

- Accession Number

- IDB-124289-000107

- Collection

- Corpus of Scottish medieval parish churches